Opening the Toy Chest: Transforming wallpaper cleaner into a squishy, delightful toy

In the early 1900s, the air in many homes was not clean. Circulating particles of coal soot and wood smoke from heaters left wallpaper with dark, grubby smudges. Homemakers made their own compound to roll up and down on the wall to remove the dirt. Kutol Products filled the need with a handy pre-made substance that sold well until the market tanked. Despair turned to joy when a nursery school teacher realized that wallpaper cleaner could be an entertaining children’s toy, a fun product dubbed Play-Doh™.

Kutol Products Opening in 1912, Kutol Products sold powdered hand cleaners and other products. Suffering a sharp downturn in business, in 1927, Cleophas McVicker was hired to shutter the firm for good. Instead, he bought the Cincinnati, Ohio company. The innovative McVicker “worked out a deal with Kroger to manufacture wallpaper cleaner, making Kutol the largest manufacturer of wallpaper cleaner in the world,” noted to “Kutol’s Story” at Kutol. (Kroger is a large American grocery chain.)

There was a snag. McVicker told Kroger executives that of course, he knew how to make wallpaper cleaner. However, he had no idea. He and his colleagues scrambled to develop the product. It was urgent. McVickers had signed a $5,000 performance contract with the retailer to ship 15,000 cases of wallpaper cleaner by a specific date. It appears that they were successful.

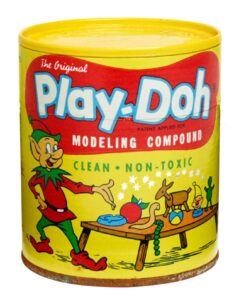

Still awaiting patent approval, the vintage can of Play-Doh(R) had a point-eared character and table of creative ideas, circa 1960s.” Mental Floss

McVicker’s brother Noah joined the company as plant manager, along with other family members, bringing new products to the sales roster. By the 1950s, cleaner heating fuels came on the market and sales evaporated for the once-popular “Kutol Wall Cleaner (non-crumbly type).” Phasing out the product, the company struggled financially, and personally.

A plane crash in 1949 claimed the life of Cleo McVicker at age 46, and his wife Irma took over company operations. She hired her son Joseph and son-in-law Bill Rhodenbaugh. Shortly after, Joseph, only in his early 20s, was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma. Surgery was unsuccessful and in 1954, radiation treatments were experimental. Somehow, McVicker recovered. However, the Kutol firm still needed a miracle.

Rescue came from an unexpected source. Joseph McVickers’ sister-in-law, Kay Zufall, was a nursery school teacher who had read an article about using wallpaper cleaner to make Christmas ornaments. Making plans for a class project, Zufall located a can of the clay at a hardware store—it was hard to find since the firm stopped manufacturing the product—and gathered supplies.

“We rolled this stuff out, and then took cookie cutters and cut out the shapes,” Zufall described in the Tim Walsh book, Timeless Classic Toys and the Playmakers Who Invented Them (Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2005). “We put little holes in the tops and then I dried them out in the oven at home.” She called McVicker and told him about the ornaments, and how she believed that the compound would be a good toy. He hustled over for a look, and excitedly told his sister-in-law, “My God, we’ll do it!” Zufall suggested calling it ‘Play-Doh.”

The formula was adjusted, replacing the harsher cleanser scent with an almond aroma. The detergent was removed and colour added. After 22 years of sales, wallpaper cleaner was out and the new Rainbow Modelling Compound was in. McVicker established Rainbow Crafts as a subsidiary of Kutol Products and launched production using equipment already in the factory, the large industrial mixers, and conveyors.

Management did not think that retailers would be interested in the moldable compound, so they aimed for the Cincinnati school board market. Packaged in nearly 4-litre-size cans, the lids indicated the colour inside—red, blue, or yellow. “Soon Play-Doh was in every elementary school in the city,” Walsh said.

Exhibiting at a 1956 convention, McVicker won his first retail customer, the Woodward & Lothrop department store in Washington, DC. Packaged as a set of three 7-ounce cans, the company added engaging colourful wrappers featuring a pointy-eared pixie. A character called “Play-Doh Pete” emerged, and later a smiling cartoon child.

Holding demonstrations of the creative fun of the colourful dough, McVicker received orders from the highly-respected stores Macy’s and Marshall Fields. Another dramatic breakthrough came the next year, thanks to Captain Kangaroo™.

The children’s television personality loved the colourful clay. Without a budget for marketing, McVicker offered Bob Keeshan (Captain Kangaroo) 2% of sales in 1957 if he would put it on his tv show once a week. Keeshan agreed. He went beyond once a week, he put Play-Doh on-screen three times a week… for years. Other shows soon began advertising the compound as well. Play-Doh was a smash hit. So many requests flooded in that it took well over a year to fill the crush of back orders.

Over four years, Rainbow Craft’s Play-Doh brought in sales of almost $4 million. “We would sell wallpaper cleaner for 34 cents a can, but Play-Doh—same stuff, same can—we could sell for $1.50,” Rhodenbaugh was quoted by Walsh. The company developed accessories to use with Play-Doh, including the still-popular Fun Factory to make shapes, ropes, and characters.

Preparing patent applications, the McVickers filed first in 1958 (that one was abandoned), then resubmitted on May 17, 1960. On January 26, 1965, US Patent 3,167,440 was issued to Noah McVicker and Joseph McVicker as assignors to Rainbow Crafts, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio. The patent stated:

“A smooth and velvety composition of matter which is soft, pliable, non-sticky, non-toxic, substantially lump free, moldable into any desired shape, and of a consistency to retain its shape.” The data added “it is non-staining and will not harm or mar desks, rugs, furniture, clothing or hands; it is non-toxic (not recommended for eating but no harm is done should a child accidentally swallow a piece of it).” Small quantities of food colourings are added, “preferably about 2 oz. (60 ml) of the blue and red and about 4 oz. (120 ml) of the yellow dyes are used in a 1000 lb (453.5 kg) batch of the composition.”

According to the present manufacturer, Hasbro, Inc. the ingredients of Play-Doh are mostly flour, water and salt. Their patent from March 2004, US6713624B1, states that the compound is made of “surfactant, starch-based binder, preservative, and retrogradation inhibitor are mixed to form a first mixture prior to adding the water to the first mixture.” Colours, scents, and other enhancements are also added.

By mid-1960s, Play-Doh was marketed in European shops in Italy, France, and England. The operation was selling over one million cans of dough a year. General Mills bought Rainbow Crafts in 1965 for $3 million. “In 1972, General Mills placed Play-Doh under the Kenner brand name, and Kenner continued to manufacture Play-Doh until the company was acquired by Hasbro in 1991,” said Shannon Symonds at Strong National Museum of Play.

The squishy modelling compound earned several awards. In 1998, Play-Doh was inducted into the Strong Museum’s National Toy Hall of Fame; the product was included in the Toy Industry Association’s “Century of Toys” list for creative impact in 2003; and the company also earned many awards over the years for advertising creativity.

Delighting children around the globe, Play-Doh™ now sells nearly 100 million units per year. In May 2018, Hasbro trademarked the unique modelling clay scent, for its “combination of a sweet, slightly musky, vanilla-like fragrance, with slight overtones of cherry, and the natural smell of a salted, wheat-based dough.” The aroma is unforgettable. That’s marketing brilliance.

(c) 2025 Susanna McLeod. This article first appeared in the Kingston Whig-Standard in April 2025.